The most important feature of scripting is its ability to reduce the amount of time it takes to accomplish a specific task. In the words of Uwe Ligges and popularized Patrick Burns’ R Inferno:

“Computers are cheap, and thinking hurts.”

In this post, I want to share how I streamline my R scripting. Hopefully, this will save you from a lot of manual labor.

Using The Command Line

My main guiding principle is to ensure my scripts run out-of-the-box from the command line. If I have to open an R Markdown file in RStudio and run it block-by-block manually, then the script is not doing its job. This means I mostly do my coding in the Sublime text editor, and I only use RStudio to test ideas, debug code, or perform exploratory data analysis. To make this happen, there is a little bit of up front overhead in setting up the script, but I guarantee you that the time savings down the road makes this approach absolutely worth it.

Directory Structure

To make file management easy for myself and be able to quickly determine where to place files, I self-impose the following directory structure for all of my projects. Note that this does not strictly follow CRAN’s package structure requirements; it is missing some required files and directories, such as DESCRIPTION, NAMESPACE, tests, and vignettes. However, in my experience, this is the absolute minimum I need to get up-and-running, so it’s good enough for me. If I need the other files, I can add them later.

my_repository/

├─ data/

├─ figures/

├─ R/

│ ├─ tools/

│ └─ my_script.R

├─ ref/

└─ README.md

If I have to work with multiple scripts, I always make sure to create subfolders within the data/ and tools/ folders so I don’t end up with a huge dumping ground of files. This is a very Pythonic style of file organization, because in R, the best practice is to have all .R files be top-level. However, when I see how overwhelmingly many files are in the toplevel of repositories like dplyr, I’d much rather break that rule to remain organized than follow it and be confused.

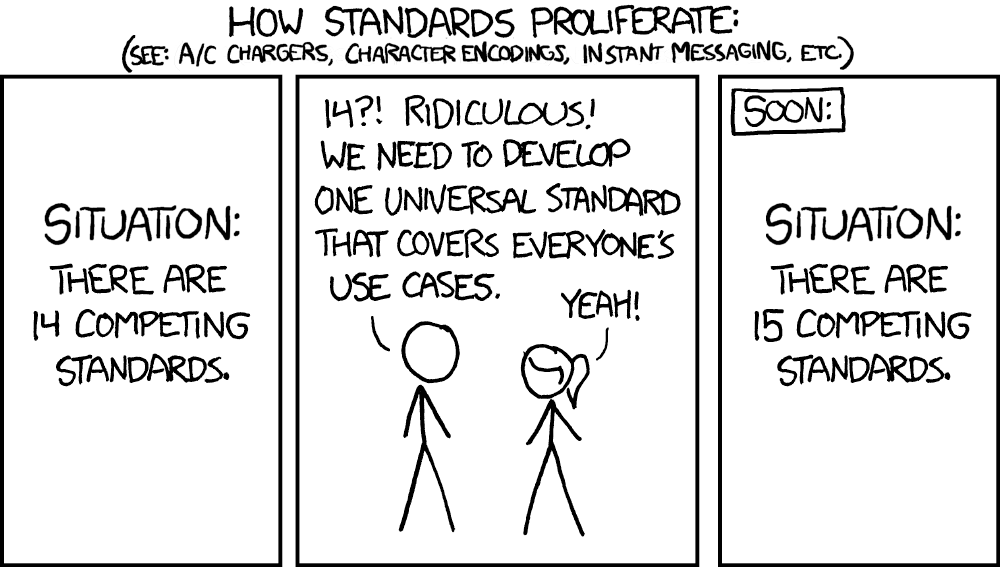

This directory structure has worked well for me, but it is not the only one. Throughout the years, people have come out with many different standards, and I don’t think there’s a consensus for script-centric repositories. For example, here is a paper describing the system that worked well for these authors that differs greatly from mine.

I think the most important thing is just to pick a system and stick with it.

However, there is one exception. If your goal is to create an R package to house reusable functions (and no scripts), which you can install and call using library(), then R does require you to use top-level .R files. This is because Roxygen2 cannot detect or document any functions in nested R directories, so they will not be installed. In this case, I recommend reading chapters 6-8 of Hadley Wickham’s R Packages book and looking at some examples of stable libraries, such as broman or harrisonRTools (modeled after broman).

Setting the Working Directory

This is one of the most useful lines of code I’ve ever written, and I include it on the top of every script above all of my library imports.

wd = dirname(this.path::here())

This line helps me to easily reference any files within my repository, like so:

# import from 'functions'

source(file.path(wd, 'R', 'functions', 'file_io.R'))

# save to 'data'

library('datasets')

filepath = file.path(wd, 'data', 'mtcars.csv')

write.table(mtcars, file = filepath, row.names = FALSE, sep=',')

Although this works when you run your script from the command line, if you’re debugging, you will still need RStudio. However, if you try to run this.path::here() in RStudio, you will get the following error:

Error in .sys.path.toplevel() :

R is running from RStudio with no documents open

(or source document has no path)

For that reason, I usually also include a code comment with the absolute path to the directory. For example, on my local machine, my personal copy of harrisonRTools repository lives in my ~/github/R folder, so the full line I have is this:

wd = dirname(this.path::here()) # wd = '~/github/R/harrisonRTools'

If I’m debugging, I can then copy and paste the script starting from the comment. You might wonder, why don’t you just use the absolute path directly? The answer is that having the program algorithmically determine its file location means you can move the entire repository around without worrying about changing all the instances where you hardcoded the paths.

Imports

Most of the time, people just use library() or source(), but this is not ideal for two reasons. First, if you have many library imports, changing the order of those imports will change which functions are loaded in your namespace. Second, for large packages like dplyr, clogging up the namespace with dplyr functions is not good for memory footprint of your program and can cause unexpected hidden behaviors. To get around this, you can use the import package to restrict your import to specific functions.

import::from(magrittr, "%>%")

import::from(dplyr, group_by, summarize)

import::from(ggplot2, ggplot, aes, geom_bar)

mean_mpg_per_cyl <- mtcars %>%

group_by(cyl) %>%

summarize(mean_mpg = mean(mpg))

ggplot(mean_mpg_per_cyl, aes(x=cyl, y=mean_mpg)) +

geom_bar(stat="identity")

To import a file from within your repository (eg. from the R/functions subdirectory), you can follow the example below using .character_only=TRUE argument, outlined here:

import::from(

file.path(wd, 'R', 'functions', 'file_io.R'),

'read_excel_or_csv', 'read_csv_from_text',

.character_only=TRUE

)

In addition to being more memory efficient, being explicit about where the functions come from also helps with traceability. When someone opens your files for the first time, they will see instantly at the top of the file what the dependencies are. Therefore, I would not recommend using the double-colon :: operator directly without the accompanying import statement at the top.

mean_mpg_per_cyl <- mtcars %>%

dplyr::group_by(cyl) %>%

dplyr::summarize(mean_mpg = mean(mpg))

Lastly, if you try to import::from a file with library() or import::from at the top, you may run into an error due to scoping, where the functions cannot access their dependencies. To get around this, there are two strategies. If you have a small number of functions to import, use import::here, which is similar to import::from, but restricts the access of the dependencies. If you have a large number of functions to import, typically from ggplot2, you should just source() the file and use library(ggplot2) in the file itself.

Command Line Arguments

Since we’re using the command line, we need to be able to pass arguments to the script when we run it. Most of the time, this means using flags to specify input files -i, but this can also be used to choose between different settings for how the script should be run or how the output should look. For handling command-line arguments, optparse is my preferred go-to library, because it is convenient to use and syntactically very similar to Python’s argparse library.

library('optparse')

option_list = list(

make_option(c("-i", "--input-file"), default='data/input.csv',

metavar='data/input.csv', type="character",

help="specify the input file"),

make_option(c("-o", "--output-file"), default='data/output.csv',

metavar='data/output.csv', type="character",

help="specify the output file"),

make_option(c("-t", "--troubleshooting"), default=FALSE, action="store_true",

metavar="FALSE", type="logical",

help="enable if troubleshooting to prevent overwriting your files")

)

opt_parser = OptionParser(option_list=option_list)

opt = parse_args(opt_parser)

One of the options I always include is a flag called “troubleshooting”, because by wrapping your save functions with this flag, you can quickly disable all the outputs and just see if your code runs. This is especially helpful if you copy and paste sections of code into RStudio, so you don’t have to worry about accidentally copying lines that will overwrite your original files.

# save

if (!troubleshooting) {

filepath = file.path(wd, 'data', 'mtcars.csv')

write.table(mtcars, file = filepath, row.names = FALSE, sep=',')

}

Logging

In the command line, if you don’t print or log anything, it will just look like nothing happened for a few seconds, and then the terminal prompt will appear again. Other times, you may get an error message, but it won’t be clear which line the error originated from. In order to get useful feedback on your script, it’s helpful to mark sections in the code. To do this, I usually put this line below my argument parsing and before any code I have for my main script:

library('logr')

# start Log

start_time = Sys.time()

log <- log_open(paste0("my_script-",

strftime(start_time, format="%Y%m%d_%H%M%S"), '.log'))

log_print(paste('Script started at:', start_time))

Then, at the end, I always include this line.

# end log

end_time = Sys.time()

log_print(paste('Script ended at:', Sys.time()))

log_print(paste("Script completed in:", difftime(end_time, start_time)))

log_close()

In between, I mark major sections of code using log_print(), so if the program does crash, by checking the last printed statement, I’ll know which section of the code crashed. For small scripts, this may not be as important, but when you have a script that tends to take >1 minute, you may want to know which part of your pipeline is currently running or to see if your script progressed at all.

Saving Files

For saving files, I always consider saving programmatically first, using functions like write.table or ggsave. I think using RStudio’s Export button should only be a last resort. Even for libraries in which it’s not obvious how you would save programmatically, it may be possible to accomplish this. For example, when I was working with chromoMap, even though the documentation recommends using RStudio and the top answer on StackOverflow is to just use a different library for the plotting altogether due to the lack of save functionality, I found that the object actually just an htmlWidget object, so it can be saved using the saveWidget command. If you’re stuck, you can always examine objects using the str command.

Saving Dataframes

One quirk of dataframes has to do with saving them. Universally, csv files should have the same number of headers as data. For example, consider the following table:

| mpg | cyl | disp | am | gear | carb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mazda RX4 | 21 | 6 | 160 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| Mazda RX4 Wag | 21 | 6 | 160 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| Datsun 710 | 22.8 | 4 | 108 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

In this table, the table headers tells you about the data below, and the index column does not include a name for the column. The csv representation of this is:

,mpg,cyl,disp,am,gear,carb

Mazda RX4,21,6,160,1,4,4

Mazda RX4 Wag,21,6,160,1,4,4

Datsun 710,22.8,4,108,1,4,1

Now consider the default output of write.table().

library(datasets)

write.table(mtcars, file = 'test.csv', sep=',')

When you open the table up in Excel, this is what you see:

| mpg | cyl | disp | hp | gear | carb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mazda RX4 | 21 | 6 | 160 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| Mazda RX4 Wag | 21 | 6 | 160 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| Datsun 710 | 22.8 | 4 | 108 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

Notice that all the column names are left-shifted relative to the data. This is because the underlying csv representation of this data is:

mpg,cyl,disp,am,gear,carb,

Mazda RX4,21,6,160,1,4,4

Mazda RX4 Wag,21,6,160,1,4,4

Datsun 710,22.8,4,108,1,4,1

In fact, when you read back into memory, read.table() will fail to recognize that the names are left-shifted, and this will easily break your code. To get around this, you have to make sure you always export with row.names = FALSE. To be honest, I’m not sure why this isn’t already the default option.

What if you need to export the rownames too? To get around this, you can move the data from the rownames to a real column, then export with the row.names = FALSE option. This following function mirrors pandas’ reset_index:

reset_index <- function(df, index_name='index', drop=FALSE) {

df <- cbind(index = rownames(df), df)

rownames(df) <- 1:nrow(df)

colnames(df)[colnames(df) == "index"] = index_name

if (drop == TRUE) {

df <- df[, items_in_a_not_b(colnames(df), 'index')]

}

return (df)

}

mtcars <- reset_index(mtcars, index_name='model')

write.table(mtcars, file = 'test.csv', row.names = FALSE, sep=',')

View(mtcars)

Nonstandard Evaluation

One of the things that bothered me a lot about R is that some functions, such as dplyr’s group_by() or ggplot’s aes(), accept and require unquoted strings. In most languages, unquoted strings are variables, and uninstantiated variables should result in this: Error: object 'x' not found. Yet in R, some functions require you to use unquoted strings. For example, consider the following example code from dplyr’s documentation:

library(dplyr)

library(ggplot2)

library(datasets)

mean_mpg_per_cyl <- mtcars %>%

group_by(cyl) %>%

summarize(mean_mpg = mean(mpg))

ggplot(mean_mpg_per_cyl, aes(x=cyl, y=mean_mpg)) +

geom_bar(stat="identity")

In some contexts, this may seem acceptable, but the subtle problem with this code is that it is inflexible. Suppose you want to compare mpg across the groups cyl, gear, and carb and then save the resulting dataframes. Doing something like this will result in an error:

groups <- c('cyl', 'gear', 'carb')

for (group in groups) {

df <- mtcars %>%

group_by(group) %>%

summarize(mean_mpg = mean(mpg))

write.table(df, file = paste0(group, '.csv'), sep=',')

}

# Error in `group_by()`:

# ! Must group by variables found in `.data`.

# ✖ Column `group` is not found.

# Run `rlang::last_trace()` to see where the error occurred.

Why does this happen? It turns out that dplyr uses a capturing expression to convert what should have been the variable group into the string "group". This is known as a nonstandard evaluation, which breaks a concept known as referential transparency, or the idea that you should be able to track variables through functions without any hidden behaviors. In the code above, we expect the function receives the value "cyl" as the input, but instead, it receieved the value "group", which is an unexpected hidden behavior. So what do beginner coders do when faced with this problem?

# example of what not to do

df <- mtcars %>% group_by(cyl) %>% summarize(mean_mpg = mean(mpg))

write.table(df, file = 'cyl.csv', sep=',')

df <- mtcars %>% group_by(gear) %>% summarize(mean_mpg = mean(mpg))

write.table(df, file = 'gear.csv', sep=',')

df <- mtcars %>% group_by(carb) %>% summarize(mean_mpg = mean(mpg))

write.table(df, file = 'carb.csv', sep=',')

Obviously, this code duplication is terrible, but how can we do better? Here are two ways to get around this limitation:

-

Using the

.datapronoun:mean_mpg_per_cyl <- mtcars %>% group_by(.data[['cyl']]) %>% summarize(mean_mpg = mean(.data[['mpg']]))This is good if you have one variable that you’re trying to replace, and it is the recommended solution for when

aes_string()was deprecated in ggplot2 version 3.0.0. In fact, this code will solve the issue posed above:library(dplyr) groups <- c('cyl', 'gear', 'carb') dataframes <- list() for (group in groups) { df <- mtcars %>% group_by(.data[[group]]) %>% summarize(mean_mpg = mean(.data[['mpg']])) write.table(df, file = paste0(group, '.csv'), sep=',') } -

Using the splice operator

!!!in conjunction with the syms function!!!syms:library(rlang) mean_mpg_per_cyl <- mtcars %>% group_by(!!!syms('cyl')) %>% summarize(mean_mpg = mean(!!!syms('mpg')))This is especially helpful if you have multiple values you want to replace. For example, if you wanted to group by both

'cyl'and'am', it would be verbose to see repeated instances of.data.# verbose mean_mpg_per_cyl <- mtcars %>% group_by(.data[['cyl']], .data[['am']]) %>% summarize(mean_mpg = mean(.data[['mpg']]), .groups = 'drop') # better groups = c('cyl', 'am') mean_mpg_per_cyl <- mtcars %>% group_by(!!!syms(groups)) %>% summarize(mean_mpg = mean(!!!syms('mpg')), .groups = 'drop')

If nonstandard evaluation encourages such bad practices, why is it included with the language, and when can it be useful? Suppose you are writing a function to modify your variable inplace (or at least give that appearance), using deparse(substitute()) to get the variable name, you can do something like this:

fillna <- function(df, cols, val=0, inplace=FALSE) {

df_name <- deparse(substitute(df))

for (col in cols) {

df[is.na(df[, col]), col] <- val

}

if (inplace) {

assign(df_name, df, envir=.GlobalEnv)

} else {

return(df)

}

}

mtcars[['ones']] <- NA

fillna(mtcars, 'ones', val=1, inplace=TRUE)

In general, nonstandard evaluation falls under the larger umbrella of metaprogramming, which is the idea of using code to analyze, parse, and generate code. This provides a lot more flexibility in what you can accomplish.

Variables

At a first glance, assigning and accessing variables may seem like such a trivial task. You’ve probably done it thousands of times. However, being familiar with the different ways variables to accomplish this will help with code readability, and on a broader scale, help you write properly scoped functions and prevent name collisions and redundant calculations.

Single Assignment

There are three main operators to perform variable assignment: the equals operator =, the assignment operator <-, and the deep-assignment operator <<-. Most of the programming languages uses the equal operator for assignment. I recently learned why this is not necessarily so in R. As explained in this blog post by Colin Fay, R came from the S programming language, which mainly used <- and _ as assignment operators and = to test equality. This also explains why CamelCase is preferred over snake_case (which I personally prefer). In 2003, the _ operator for assignment was removed, but the conventions stuck.

In the global environment, the arrow operator <- is interchangeable with the equals operator =, but within functions, they differ in their scope and precedence. The equals operator = is limited in scope, because it only peforms argument passing, whereas the arrow operator performs argument passing and object assignment. Consider the function add_one:

add_one <- function(x) {

return(x+1)

}

Depending on how you store call the function, x can be accessed after use.

# 1 is temporarily passed to x

add_one(x = 1)

# 1 is assigned to x and is accessible after running the function

add_one(x <- 1)

Now consider the function add_one_to_one:

add_one_to_one <- function() {

x = 1 # or equivalently, x <- 1

return(x+1)

}

add_one_to_one() # x is not accessible globally

Neither using the equals operator nor arrow operator will allow you to access x outside the function. However, the double-arrow operator <<- does.

add_one_to_one <- function() {

x <<- 1

return(x+1)

}

add_one_to_one() # now x is acessible

This can be used to modify variables in place, because if you instead returning the variable within the function, then assigning the return result outside the function, due to R’s copy-on-modify system, this will result in R copying your data twice! Here’s an example from Hadley Wickham demonstrating this principle, in which updating a particular value in a dataframe results in it being copied three times per iteration!

Mutli-Assignment

The zeallot library allows you to access the %<-% operator to perform multi-assignment, which can be helpful if you are trying assign from a function that returns multiple values or if you are assigning multiple variables within functions and you want to make your code more compact.

library('zeallot')

c(a, b, c) %<-% c(1, 2, 3)

Multi-Argument Passing

Related to multi-assignment is a nifty function called do.call, which allows you to pass a list of arguments to a function rather than typing it out.

add_a_b_c <- function(a, b, c) {

return(a+b+c)

}

# type out all the arguments

result <- add_a_b_c(a=1, b=2, c=3) # 6

# pass a list of arguments

result <- do.call(

add_a_b_c,

list(a=1, b=2, c=3)

) # 6

Now you can store multiple default options for your function separately from the function itself.

Logical Operators

In a string of logicals, for example x & y & z, R evaluates all the arguments left-to-right and then returns the final result. In these kinds of statements, which are typically used for case switches, if any of the values are FALSE, then the entire result is FALSE. In this case, if you use && instead, for example x && y && z, R will stop the evaluation as soon as it finds the first FALSE. This can be a minor speed-up if you’re computing something many times, but most of the time, it doesn’t matter.

Another thing you might consider is always using the full word TRUE and FALSE to represent logicals, because they are protected. I’ve seen T and F in various scripts, and this is bad practice, because it decreases readability and makes search much more difficult. It’s also possible to overwrite these, because they’re not protected. For example, try running T <- FALSE.

Subsetting Dataframes

Although many people prefer using the dollar-sign $ operator due to its autocomplete functionality in RStudio, for scripting, the double-brackets method is superior, because being able to pass a string means you can bind that string to a variable and pass it through a for loop. Also, strings show up in green in Sublime (red on this blog), making them far easier to visually identify.

library(datasets) # load the mtcars dataset.

# dollar sign

mtcars$mpg

# double brackets

mtcars[['mpg']]

The problem with the dollar-sign operator is that if you ever want to swap out the variable, you will need to do so manually, making it inflexible.

Basic Data Structures

Understanding the basic data structures of R is essential in essential ensuring that your code runs optimally and does not have any unnecessary side-effects.

Data Types

R has two different numeric kinds of data types, integer and double. By default, any number you type is a double, which takes up more memory. If you want it to be an integer, you can use the L suffix, as explained here in the R Language Definition

Lists

In Python, a list is implemented as a dynamic array, meaning that appending it has a time-complexity of O(1). This works, because under the hood, the list pre-allocates an anticipated amount of space and only grows it when the max size is reached. Furthermore, when you append your object (stored in a variable) to the list, it doesn’t copy the data into the list, it simply adds a reference to your object into the list. This is known as pass by assignment, and it makes the append operation extremely cheap. For that reason, in Python, appending into a list is considered good practice, because it is easy-to-understand and there are no hidden inefficiencies.

results = [] # instantiate an empty list

for file in in files:

df = pd.read_csv(file)

results = do_something(df)

results.append(df)

Therefore, I was suprised to learn that actually, R does not work that way. Instead, R primarily uses copy-on-modify, meaning that when you append a list, the entire list will get copied. This can lead to a lot of unnecessary copying of data, which causes significant slowdowns.

Fortunately, there is a simple workaround for this, by using an R environment. First, instantiate the R environment, then at the end, convert it the environment back into a list.

library('dplyr')

groups <- c('cyl', 'gear', 'carb')

dataframes <- new.env()

for (group in groups) {

dataframes[[group]] <- mtcars %>%

group_by(.data[[group]]) %>%

summarize(mean_mpg = mean(.data[['mpg']]))

}

dataframes <- as.list(dataframes)

Dictionaries

In Python, a dictionary or hash table is a key value pair in which the key is unique and the lookup time is O(1). This data structure is incredibly useful for things like control flow statements, storing default arguments, and working with non-rectangular data such as customer histories. In order to be a proper hash table, insert and search operations need to have a time complexity of O(1). So when I saw that a named list somewhat mirrors Python dictionaries, at first, I was excited. This means I can use it to simplify my code, right?

simple_lookup <- setNames(

nm=c(1, 2), # keys

object=list("value1", "value2") # values

)

simple_lookup[['1']] # "value1"

Right…? No. Actually, as it turns out, R does not have a base hash table implemented, and a named list is not a real hash table. In fact, it has an O(n) linear search, which is terrible. To get a proper O(1) lookup table, you need to instantiate an R environment.

# instantiate directly

lookup_table <- rlang::env(

"1"="value1",

"2"="value2"

)

# convert an existing named list

lookup_table <- new.env(hash = TRUE)

list2env(

as.list(

c("1"="value1",

"2"="value2")

),

envir=lookup_table

)

However, R environments still suffer from the issue of only allowing characters as keys. To create hashtables using non-standard keys like integers, dates, or vectors, there are libraries like r2r and hashmap that enable this functionality. Just be aware that according to this blog post, if your dictionary only uses character keys, you will get better performance by using using R environments directly, so only call a library if you really need nonstandard keys.

Outro

The examples included in this post are a result of much trial-and-error and deliberate practice. They provide a template to start getting away from the manual labor of interacting with RStudio and more toward constructing standardized automatic data analysis pipelines, which will ultimately save you a lot of time. However, this barely skims the surface on what R can do. For more information on writing better code, I highly recommend reading this chapter from Hadley Wickham’s Advanced R. To see how I construct my R projects, please see my Github.

I hope you found this insightful, and I will see you in the next blog post!